Elon Musk has recently gotten a lot of press for reiterating the famous Simulation Argument, first espoused by Oxford’s Nick Bostrom, which loosely speaking states that we are almost certainly living in a simulation. Musk even went so far as to claim that the argument is virtually (pun intended) bulletproof, ironclad, without error, and the like. In a recent conference, he begged his audience members to point out the flaws and was met with the silence of the class in awe of its head, lulled into tacit acceptance of whatever the imposing authority expounds upon. Though he is assuredly a towering intellect, this argument of his, I think, is in error. Let me be more precise: I believe that his argument is invalid, despite the fact that I am inclined to agree with its conclusion. In other words, I am sympathetic to the idea that we are living in a simulation, though I do not believe that his argument demonstrates anywhere near the level of certainty to be attributed to it that he claims. To summarize the crux of my objection, I think that it is a mistake for us to use the reality that appears to us as a standard from which to reason about probabilities that relate to the world that is outside of ours. In the paragraphs that follow, I will hope to make this argument clearer by referring back to Kant’s revelation regarding the metaphysics and epistemology of transcendental idealism.

Let us first re-iterate his argument in as much detail as we have space for before proceeding to identify its weakest link. To summarize: if we grant that a fraction of all post-human technological civilizations will eventually create “ancestor-simulations” that are indistinguishable from reality and inhabited by conscious minds, then we very quickly realize that these sorts of simulations must vastly outnumber the one base reality in which all these simulations are embedded. Therefore, reasoning from an a priori point of view, the probability appears to greatly favor the situation of us living in one of these ancestor simulations constructed by our far-flung descendants. In the original paper by Nick Bostrom, the argument is crystallized into the following three propositions, at least one of which is claimed to be necessarily true:

(1) The fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage is very close to zero; (2) The fraction of posthuman civilizations that are interested in running ancestor-simulations is very close to zero; (3) The fraction of all people with our kind of experiences that are living in a simulation is very close to one.

So, here we can see that the argument hinges on the presumed implausibility of statements (1) and (2). We find no a priori reason to preclude civilizations from advancing beyond the stage we currently happen to have reached. Similarly, there does not seem to be any particular reason to believe that these civilizations will have objected so unanimously to the creation of ancestor simulations so as to render that act a rarity. By this line of reasoning, we are seemingly led to the peculiar, and somewhat unsettling, conclusion that we are almost certainly the inhabitants of just such a simulation.

I would like to poke at this argument specifically at the point where it claims that statistics from our reality (simulation or otherwise) can be used to then make inferences regarding all “actual” people having our kind of experiences. But before I do so, let us briefly examine a different objection that has been made with respect to this argument.

Other objections to the argument stem from philosophy of mind and point the finger at the proposition that being indistinguishable from reality is a sufficient condition for conscious minds. I am not in Ned Block’s camp in believing that a simulation of a mind cannot possibly be a real mind. I see no reason why a simulation of an autonomous information processing system of sufficient complexity and integration of information could not one day achieve the exalted state of a conscious and sentient being. I cannot find any way to argue for a privileged status of neuron based consciousness that deprives all other physical substrates of sentience. If we take a computationalist account of consciousness, then it becomes clear that what is important is the presence of the requisite information processing functional structure, regardless of how this computing system is instantiated physically. Therefore, I will dismiss this superficial criticism and proceed to a slightly deeper level of argument. My objection to the simulation argument will require us to re-examine the mighty Immanuel Kant and his revelation as to the transcendental idealism that has been so influential to modern philosophical thought.

Kant’s magnificent triumph, as nicely summarized by the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, has been to pioneer the distinction between things as appearances and things as they really are. This dichotomization hinges on the recognition that space and time are to be thought of as our operating system — or in his terminology, the forms of our intuition or experience. These, in addition to causality, together serve to provide us with a formal structure by which to organize reality, but which do not reflect reality as it stands independently of our representation of it. Therefore, our particular manner of perceiving reality ought to be divorced from the true nature of whatever it is that appears to us through our mentally imposed lens of spacetime. I have often found in expressing this realization to people that there is a knee-jerk opposition to its deeper ramifications. It seems that we have an inherent belief in the empirical reality of the world that we perceive and that we stubbornly wish to view ourselves as passive observers merely receiving information regarding that reality. In my mind, such a view is needlessly wasteful in its seeming duplication of reality, one copy of which is real, and the other of which is our mental representation of it. It seems far more plausible to me to view the perceptual world as a construct that our mind actively creates, and the real world as something of an inherently different nature.

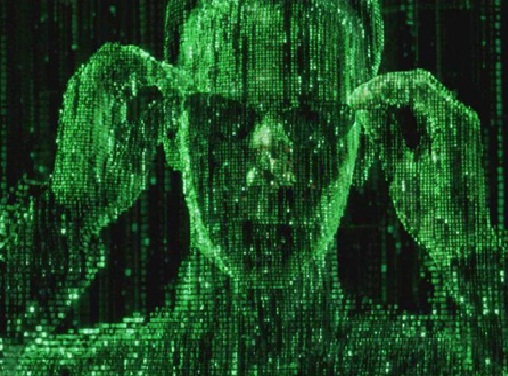

I have always wanted to interpret Kant’s revelation using the contemporary metaphors and symbols that are available to me — as I alluded to in the previous paragraph. As such, I have often likened his notion of things-in-themselves as corresponding to the codebase of reality, whereas what he calls representations or appearances are their spatiotemporally rendered manifestations. In fact, there are many analogies we can use to describe this state of affairs, and indeed, it arises from our modern day conception of information theory. We see this in the distinction between genotype (the genetic information stored in a strand of DNA) and phenotype (the organism’s physical and behavioral characteristics expressed from the DNA), the distinction between a concept and a percept, and also in digital signal transmission where complete sensory experiences can be turned into sequences of ones and zeros and then decoded back into the original representational form. Thus, at the risk of providing too literal an analogy, we could simply re-interpret Kant’s theory in modern terms and state that we are thus necessarily living in a simulation, albeit one that is generated by the space-time-causality machinery of our mental information processors. Accepting this and following the line of reasoning that he laid out, we would thus be forced to abstract away the particularities of spatiotemporal causality if we ever wished to ponder the true nature of the world-in-itself. Herein lies my main contention with Bostrom’s argument.

From here, I’d like to briefly mention another famous philosopher that I am greatly inspired by and attempt to tie his theory into our current conversation. Ludwig Wittgenstein claimed to have been inspired by the great Immanuel Kant and produced a theory of language that offered an interesting perspective on the issues we are now touching upon. In his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, he provided seven cryptic and illuminating statements that lead to the ultimate recognition that “what can be said at all can be said clearly, and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence”. In this, he provides a linguistic parallel to Kant’s great metaphysical triumph. As such, the epistemology that underlies both seems to admonish should we choose to theorize too specifically about things that lie outside the scope of our knowledge. And herein lies the kernel of the objection I wish to raise: if we grant that our perceptual system operates by constructing for us a simulation, then we are restricted to reason within its boundaries. Another way to say this is that we are not allowed to pick ourselves up by our bootstraps and elevate our perspective to the world outside our simulation. We are helplessly trapped inside this epistemic bubble that, nevertheless, so vigorously teases its reality to us.

Thus, with regard to the Musk-Bostrom argument, we can now state the following. I will grant the first two premises of the argument, namely that the fraction of human-level civilizations that reach a posthuman stage is high, and that the fraction of posthuman civilizations that are interested in running ancestor-simulations is similarly high. However, I would argue these probabilistic intuitions that are yanked out from the empirical world that we are already living in cannot then be used to make any kind of claims about a world beyond ours. We would be wise to heed the word of Kant and Wittgenstein, among many others, that we must remain agnostic as to the world that exists outside of our perceptual simulation. Note that I am not saying that we are almost certainly NOT living in an ancestor simulation, in antithesis to the Musk-Bostrom claim. Rather, what I am saying is that one cannot make such claims at all, because they require us to provide specific assertions regarding the mode and existence of the world-in-itself. Following in the tradition of transcendental idealism, I find myself forced to treat all such claims as tentative at best, and never to be able to allocate to them any notion of probability, seeing as I am in essence trapped behind an epistemic horizon.